Have you ever wondered why the UK tax year ends on 5 April? This intriguing aspect of British bureaucracy originates not within Britain itself but begins in Ancient Rome. Intrigued?

46BC: Ancient Rome

Julius Caesar introduced the Julian Calendar in 46BC which aimed to closely emulate the solar year, consisting of 365.2422 days. Note, not precisely the 365 1/4 that we are all taught at school. That extra 0.0078 will become significant later.

The Julian system accounted for this quarter-day surplus by incorporating an extra day every four years—the leap year—into February, thereby aligning the calendar year with the Earth's orbit around the Sun.

To instigate the change during the year 46 BC, Caesar added two months to the calendar, creating what would become known historically as the "annus confusionis" or the year of confusion, resulting in a year that lasted 445 days.

1582: Rome

Despite its intentions, the Julian Calendar was flawed, miscalculating the solar year by 0.0078 (11 minutes and 13.92 seconds per year), which amounted to a full day's discrepancy roughly every century. By the 16th century, this error had caused the calendar to drift by approximately 14 days. This misalignment had significant ramifications, particularly for the Roman Catholic Church, as it impacted the determination of Easter.

Pope Gregory XIII issued a papal bull - inter gravissimas - on 24 February 1582 which rectified the problem and led to the creation of the Gregorian calendar. The leap year rule was refined such that no years divisible by 100, except those divisible by 400, would be leap years, effectively curbed the century-long drift. Hence the year 2000 was a leap year (as it is divisible by 400), but the year 1900 was not.

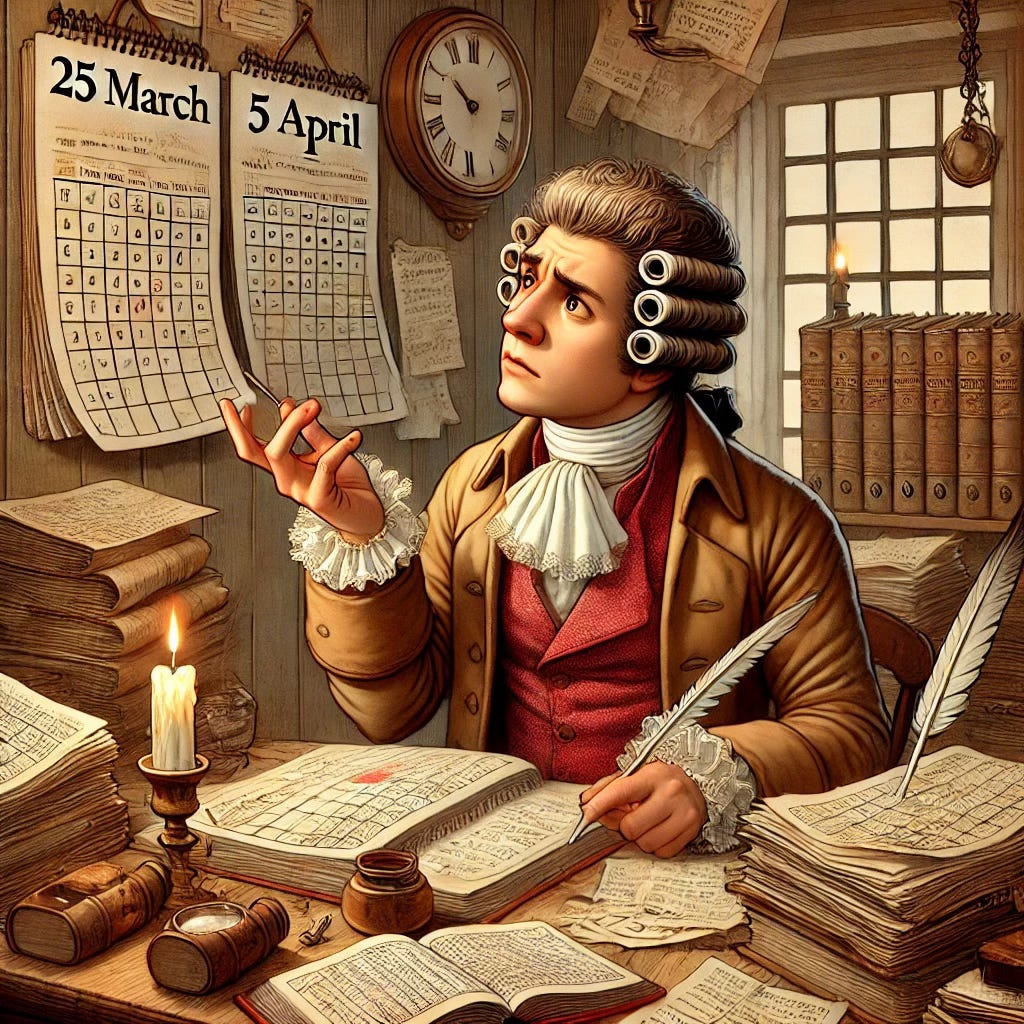

Choosing to anchor the calendar's reset to the year 325 AD—the time of the Council of Nicaea, where the method for determining Easter was established—Gregory XIII decreed the removal of only 10 days. Thus, in October 1582, the calendar leapt from the 4 October to the 15 October, realigning Easter with the spring equinox.

1752: England

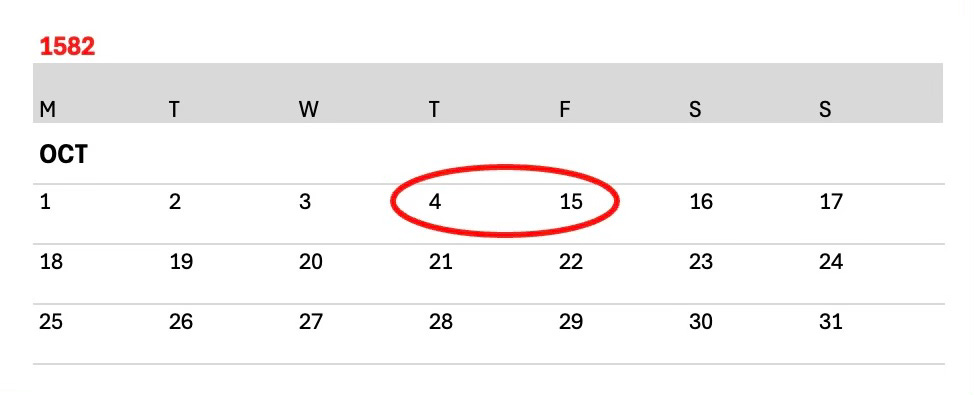

The adoption of the Gregorian Calendar was not uniform. Protestant nations, including Britain, were initially resistant, perceiving it as a Catholic innovation. It was not until 1752 that Britain aligned with this calendar system, by then necessitating an 11-day adjustment, hence why 2 September 1752 was immediately followed by 14 September 1752.

The tax year for 1752/1753 was extended by the eleven 'lost' days, moving the tax year end from 25 March to 5 April.

Simultaneously, the British government also decided to shift the start of the legal year from Lady Day, 25 March, to 1 January, in a bid to synchronise with the rest of Europe.