Financial control is something many of us strive for—it represents security, independence, and stability. In fact, taking control of one’s finances is often encouraged as a cornerstone of personal and professional success. But when does control cross the line into domestic abuse? And how can we, as professionals, recognise the warning signs?

“One in six women in the UK has experienced financial abuse in a current or former relationship1”

This article explores the pervasive nature of economic abuse, how it manifests, and the critical role financial professionals play in identifying and addressing it. By recognising the patterns of financial abuse, accountants, bankers, and other professionals can become key allies in safeguarding vulnerable individuals and helping to restore their financial independence.

What is Economic Abuse?

Economic abuse is a form of coercive control, where an abuser manipulates, restricts, or exploits financial resources to trap their partner in a state of dependence. This insidious behaviour goes far beyond financial hardship—it is about wielding power, exerting control, and systematically stripping away a person’s autonomy. Victims may be denied access to their own money, forced into debt, or prevented from earning an income, leaving them financially incapacitated and unable to escape their abuser.

Recognised as a form of domestic abuse, economic abuse is not only devastating but is also a criminal offence in many jurisdictions. In the United Kingdom, the Domestic Abuse Act 2021 explicitly identifies economic abuse as a behaviour that substantially affects a person’s ability to acquire, use, or maintain money or other resources. In the United States, the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) similarly acknowledges economic abuse as a form of domestic violence, ensuring that survivors are protected and perpetrators held accountable.

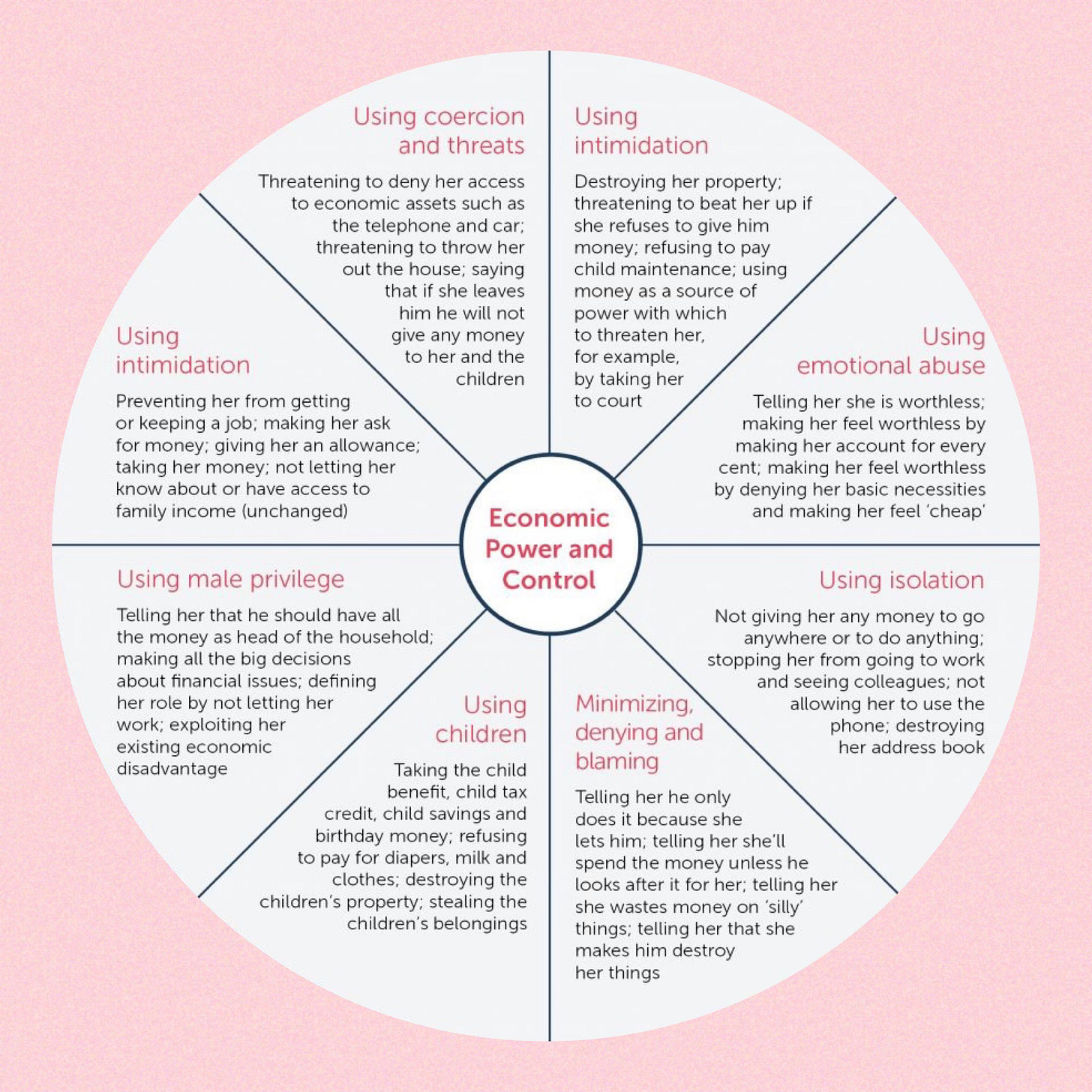

The Duluth Model, as represented in the widely recognised Emotional Abuse Wheel, provides a compelling visual framework for understanding the various forms of abuse, including economic abuse. This model highlights how different abusive tactics—such as isolation, intimidation, and financial control—interconnect to reinforce the abuser’s power and control.

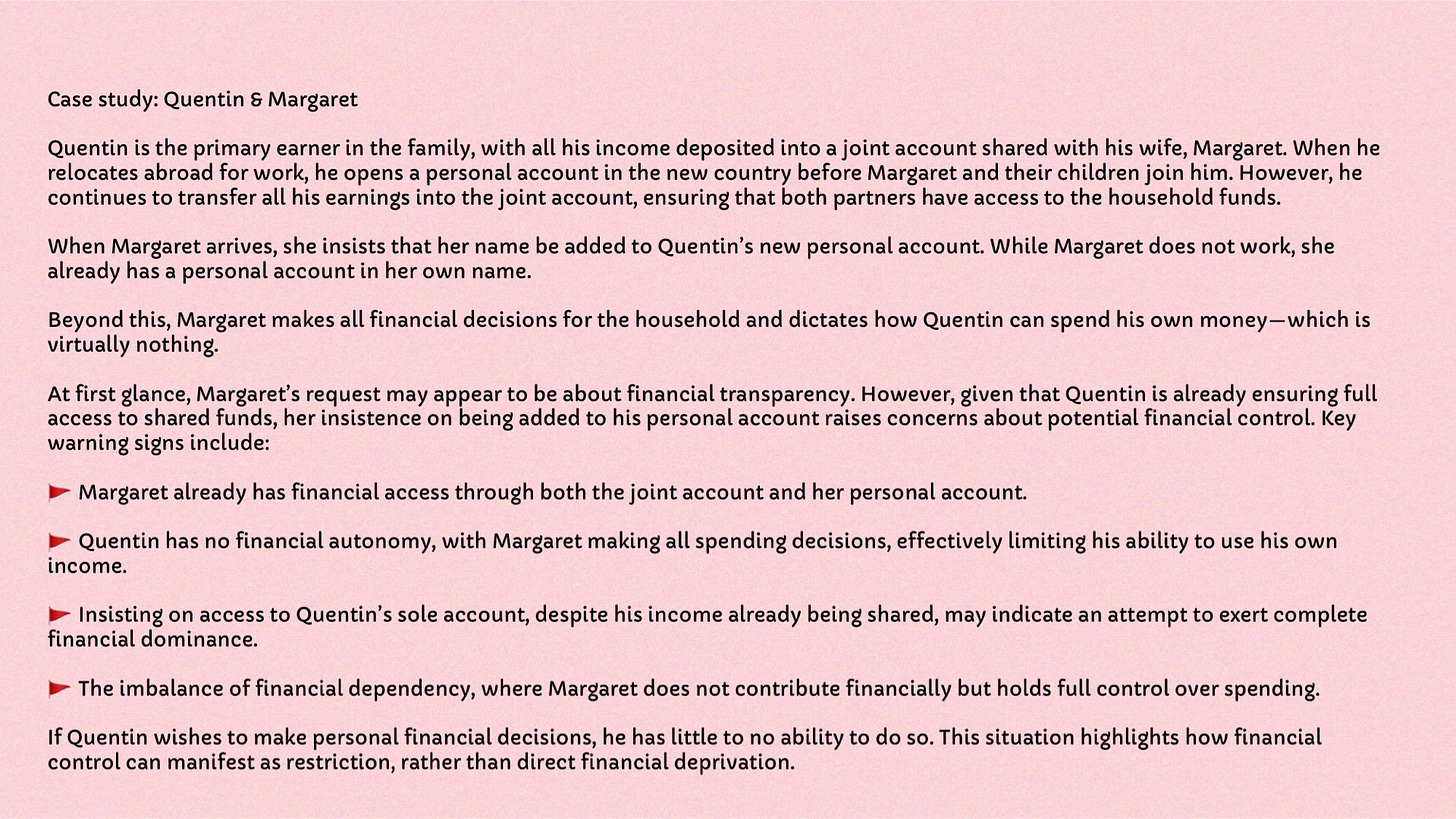

While the wheel of abuse is often centred on female victims, it is important to recognise that financial abuse can be perpetrated by women and may also target the primary earner in a relationship. The case of Quentin and Margaret illustrates a scenario in which Quentin experiences financial deprivation, a form of economic abuse.

Throughout this article, true case studies are presented in an anonymised form and without sources to safeguard the identities of the individuals involved. No matter how improbable they may seem, each scenario reflects a real occurrence.

Identifying the Red Flags of Economic Abuse

Unlike physical abuse, financial abuse leaves no visible scars, making it particularly insidious. However, there are key indicators that financial professionals can look out for when assessing a client’s or employee’s financial autonomy and wellbeing

Accountants

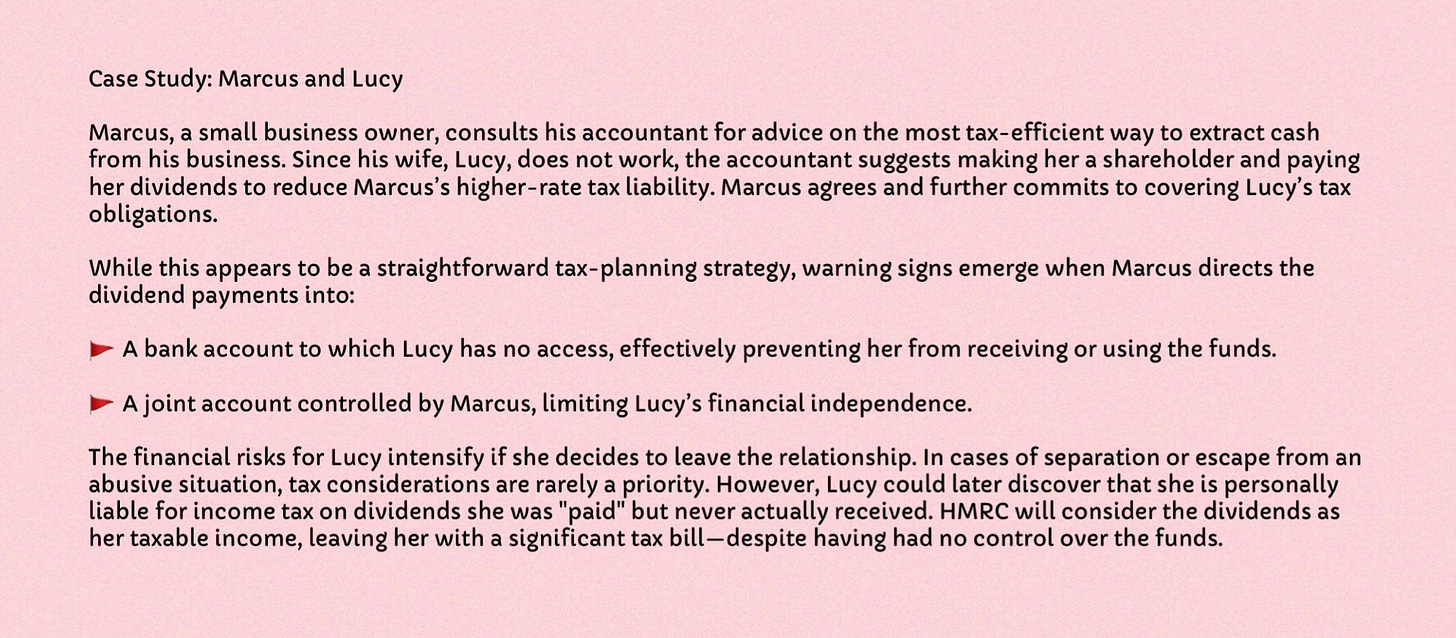

Accountants have a unique vantage point when reviewing a family's financial affairs. Warning signs include:

Only one partner actively participating in discussions, while the other remains absent or silent.

A partner insisting on being present for all financial decisions, even those concerning the other partner’s sole assets or liabilities.

The individual never attending meetings alone, suggesting potential coercion or control.

Bankers

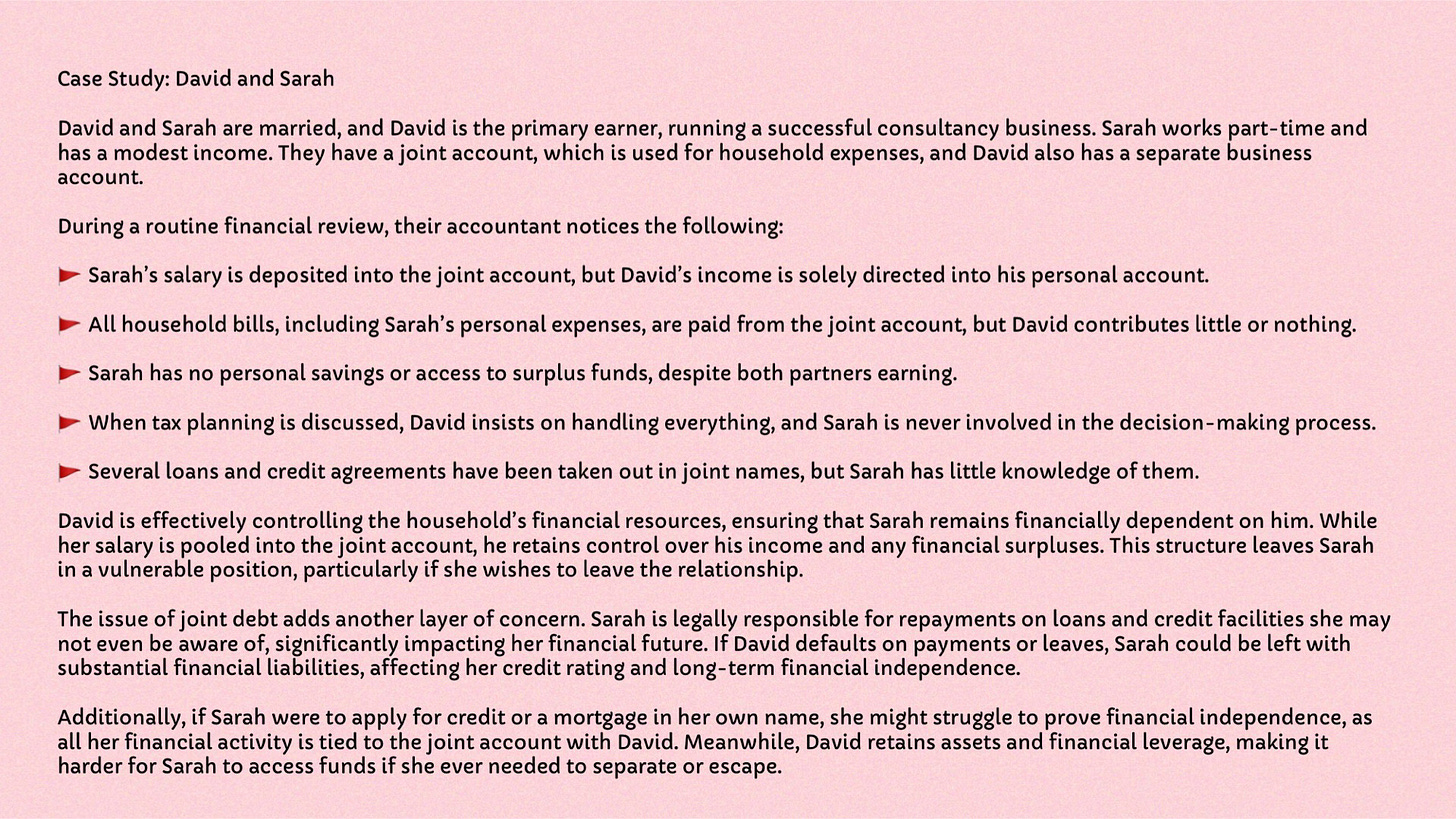

Banking professionals frequently handle financial transactions that may reveal signs of economic abuse, such as:

A joint account where only one partner makes transactions, while the other has limited or no access.

An individual having no sole account, relying entirely on a joint account controlled by their partner.

Household bills being paid exclusively from one partner’s sole account, despite both individuals having income.

The customer never visiting the branch alone, raising concerns about financial independence.

Significant debt taken out in one partner’s name, with no corresponding liability for the other.

“Half of young women don’t recognise their partner taking their money as a form of economic abuse while victim-survivors say being prevented by abusive partners from learning new skills hinders their re-establishing in the workplace.”2

Employers

Employers can also detect financial abuse through payroll patterns and employee behaviour. Red flags include:

Salaries being deposited into an account that does not belong to the employee, particularly a partner’s account.

Salaries being directed into a joint account rather than the employee’s personal account. While salary payments into joint accounts may seem customary in long term relationships, employers cannot presume to understand the intricacies of an individual’s personal circumstances. Given the prevalence of financial abuse, salaries should be paid into accounts solely in the employee’s name to protect their financial independence.

A notable discrepancy between an employee’s income and their apparent lifestyle, indicating potential financial control or exploitation.

By recognising these warning signs, financial professionals can take steps to support victims, signpost them to relevant resources, and ultimately contribute to breaking the cycle of economic abuse.

Dealing with victims

The 2021 Financial Abuse Code3 provides a comprehensive framework for financial institutions to identify, support, and protect individuals experiencing financial abuse.

At its core, the Code outlines key measures that can be taken to assist victims, including:

Secure Correspondence: Sending communications to a safe house or refuge, recognising that victims often flee without a permanent address.

Flexible Identification Requirements: Accepting non-mainstream documents as proof of identity, as abusers frequently destroy official records.

Transparency on Financial Holdings: Informing victims of any assets or liabilities held within the organisation in their name, as they are often unaware—particularly of debt incurred without their knowledge.

No Direct Contact with Abusers: Crucially, the Code states that victims should never be required to engage with their abuser.

Has your organisation truly embraced this Code? Commitment extends beyond merely signing up—have your employees received adequate training to recognise and appropriately handle situations involving financial abuse?

GDPR - General Data Possession & Restriction

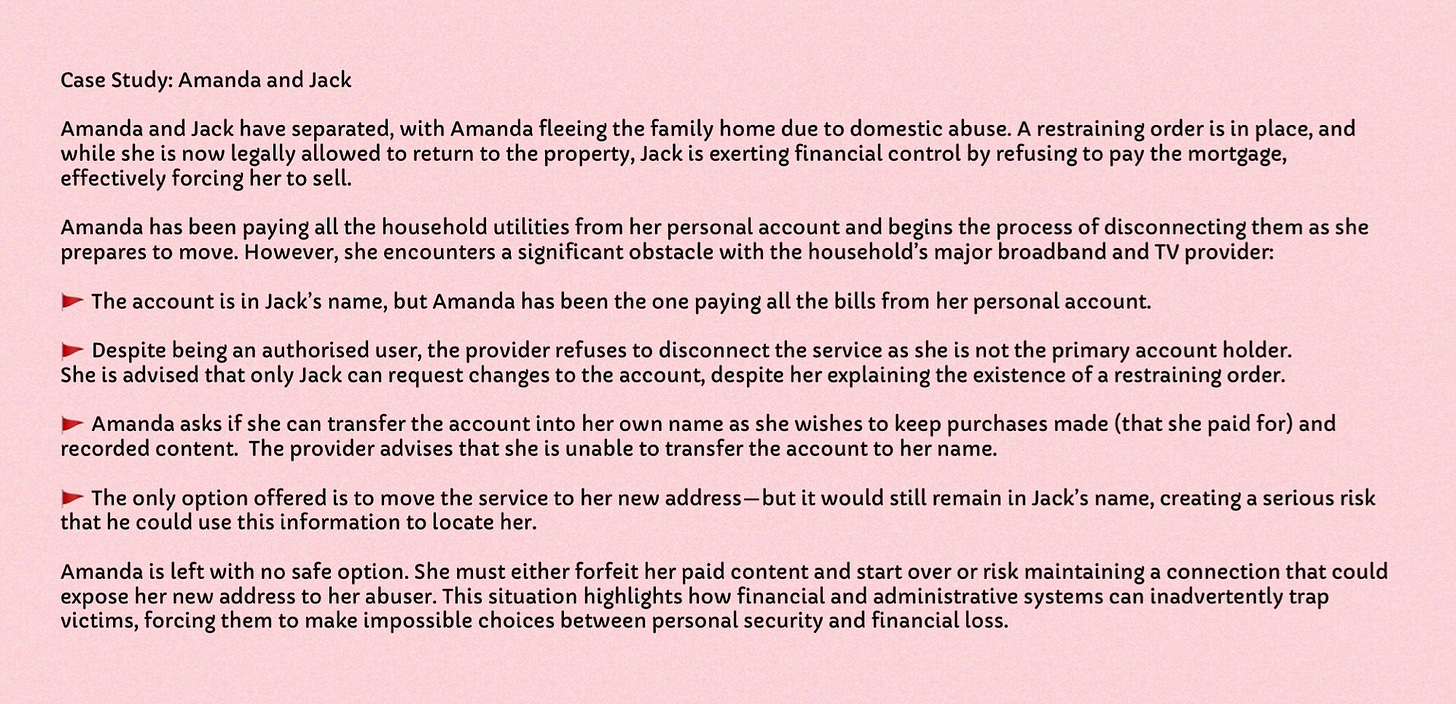

The case of Amanda and Jack highlights the unintended consequences of data protection regulations when rigid policies override safeguarding concerns. While the service provider is technically complying with General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) by restricting account changes to the named holder, this approach fails to account for Amanda’s specific circumstances—including a restraining order and her financial responsibility for the account. As a result, the system designed to protect personal data is instead being used as a tool for possession and restriction, leaving Amanda vulnerable.

GDPR is intended to safeguard individuals' data, yet in this case, it effectively prevents Amanda from safeguarding herself. If she moves the service to her new address under Jack’s name, he could exploit this information to locate her, putting her safety at risk. This demonstrates the urgent need for service providers to balance data protection with safeguarding responsibilities, ensuring that financial and digital control cannot be weaponised against victims of abuse.

However, GDPR provides little protection against abusers, who often have comprehensive knowledge of their partner’s personal information. In one instance, a victim returned home to find the property ransacked—a locksmith from a reputable firm had inadvertently granted access to the abuser’s sister, who successfully impersonated the victim using details supplied by the perpetrator. Crucially, the victim had already removed the abuser from the account, preventing him from gaining entry in his own right. This underscores the paramount importance of staff training, ensuring that security protocols are sufficiently robust to mitigate the risks faced by survivors of abuse.

Pathways to Support

Recognising the signs of financial abuse is the first step toward seeking help. Whether it affects you or someone you know, accessing the right support is crucial. Surviving Economic Abuse4 provides extensive resources and guidance on accessing support.

If you suspect that your partner or the partner of a close friend, family member, colleague, or neighbour; may have an abusive past, you can request a disclosure under Claire’s Law5 (the Domestic Violence Disclosure Scheme) in the UK by contacting 101 or visiting your local police station. Through the ‘Right to Ask’, you can apply for a disclosure if you have concerns. The process typically takes up to 28 days, though urgent cases may be expedited.

If a relevant history of domestic abuse is discovered, the police will confidentially arrange a face-to-face meeting with the victim to share necessary details, such as previous convictions, police warnings, or patterns of abusive behaviour, but only if such disclosure is deemed essential for the individual's protection.

Additionally, the Economic Abuse Toolkit6, developed by the Fairness Group, offers valuable guidance on recognising and responding to economic abuse. Although originally designed for public sector debt recovery, its principles can be effectively applied to any organisation. By training staff, developing safeguarding policies, and collaborating with specialist organisations, businesses can integrate these recommendations effectively.

Businesses can integrate its recommendations by training staff, developing safeguarding policies, and collaborating with specialist organisations to better support victims.

Organisations have a pivotal role in breaking the cycle of economic abuse and ensuring that financial systems do not inadvertently contribute to further harm. It is crucial that firms make financial abuse training compulsory to better support victims and prevent economic abuse within their spheres of influence.

Surviving Economic Abuse | March 2020

The economic abuse threat in the UK: how employers can support their people | Jane Portas | 9 Dec 2021

I need help | Surviving Economic Abuse

The right to know if your partner has an abusive past | Claire's Law

Economic Abuse Toolkit | 20 December 2023